The mask requirements are largely off in New Orleans and the rest of Louisiana, but the COVID-19 threat is by no means over. Instead, the calculations for personal risk have only become more complex.

You can take your mask off if you’re fully vaccinated — a move New Orleans Mayor Latoya Cantrell announced last week. But there’s also no enforcement for those who haven’t been vaccinated and leave the mask at home. You won’t know whether the maskless person next you has had all their jabs, or just doesn’t want to wear a mask anymore. For people with children or medically vulnerable family members, the question is even more important. And it remains unclear whether or how much vaccinated people might still spread the coronavirus.

As the state shifts into a new phase of masklessness, the data shows that COVID-19 not only remains a threat here, but an uneven one across the state.

“This is not going to end. There's no eradicating it,” said Susan Hassig, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Tulane University.

Louisiana has entered what data analyst Jeff Asher calls “the long plateau” of the lowest rates of death from COVID-19 since the pandemic began.

“Still a very dangerous disease that's still taking lives, but at this point, it is, in theory, a preventable disease for most people,” Asher said.

And a familiar echo is coming from the Louisiana Department of Health: Loosened restrictions can always be tightened again.

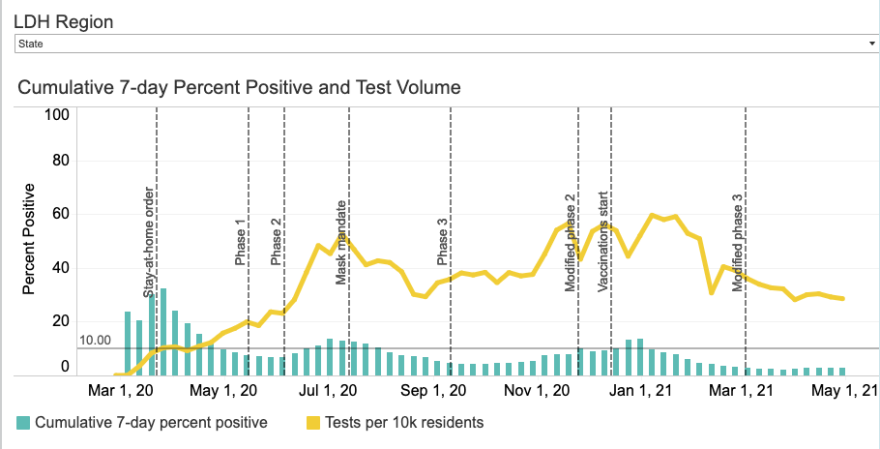

“As cases continue to stay low, we should feel comfortable relaxing regulations,” said Dr. Joseph Kanter, the public health officer. “With the caveat that if cases tick back up, we're ready to put masks back on distance again, do what we need to do to bend the curve, like we have multiple times at this point.”

That’s a possibility, given the state’s sluggish vaccination rate.

There are a number of ways the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention measures vaccination pick-up, and by all of them, Louisiana ranks among the bottom. So does the South.

When measuring the percentage of the population that’s had at least one dose of the vaccine, Louisiana is in the bottom three — only slightly ahead of Mississippi and a hair’s breadth behind Alabama. In all three states, about one in three people has at least begun the vaccination process.

That’s compared to a national rate of 47.5 percent, closer to one in two people. Alabama’s rate is 34.7 percent, Louisiana is at 34 percent, and Mississippi — with the lowest rate in the nation — is 32.5 percent.

That means that when the CDC and other national organizations talk about the state of the pandemic nationally, it’s not directly applicable to the South, especially messaging around changing restrictions in the wake of the vaccine rollouts, Hassig said.

In the South, “they're not moving to open, they're already open,” Hassig said, “and they're not anywhere near vaccination levels that are consistent with the way they've opened.”

Susanne Straif-Bourgeois is an infectious disease epidemiologist at Louisiana State University, said that vaccination rates are even worrying among groups where you might expect the opposite, including health care workers.

“And the other problem is you cannot mandate it, because then you would lose a lot of your staff and hospitals have staffing shortages,” she said.

The picture for Louisiana would be far worse if it weren’t for Orleans and Jefferson parishes.

For those two parishes alone, 43.6 percent of the population has had at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine.

For Louisiana minus those two parishes, the figure plummets to 26.2 percent of the population.

That could result in a relatively high level of protection in the Crescent City compared to greater risk elsewhere.

“We may get community immunity in New Orleans, in Orleans Parish,” Hassig said.

Kanter thinks the variations in coronavirus risks could get even more granular.

“I think you're gonna find as time goes on, there will be very large degrees of protection in certain communities, certain neighborhoods, and less protection in others,” he said.

Even within Jefferson and Orleans, vaccination rates differ widely based on race.

In Orleans, where Black residents make up two-thirds of the population, the figures are closer: about 43 percent of white residents and about 46 percent of Black residents have had at least one vaccine shot.

In Jefferson, where the population is roughly reversed, only about 22 percent of Black people have had a jab, compared to 62 percent of white people.

Since the fall, younger people have accounted for the bulk of new COVID-19 cases. There have been more cases in people aged 18 to 29 than any other age group, and people 30 to 39 years old have the second-highest number of cases. Collectively they account for 36.7 percent of positive tests reported to the state.

And until children were added to the list of those eligible for a vaccine shot last week, people aged 18 to 39 also accounted for the fewest vaccinations.

That also varies across parishes. In Region 1 of the health department, which covers the metro New Orleans area, young people are more likely to have had at least one vaccine shot.

Among those 18 to 29 years old, nearly 13 percent have had a vaccine shot, compared to just under 10 percent statewide.

For those aged 30 to 39, that jumps to over 15 percent in Region 1, compared to 11.5 percent across Louisiana.

“Most of those people that will get infected in those younger age groups probably won't get sick,” Hassig said. “So it's not going to show up really abruptly or aggressively in hospitalization.

“But that doesn't mean we don't have a problem. And it particularly doesn't mean we don't have a problem because of the variants,” Hassig said. “And that's what I'm most concerned about.”

The health department has identified cases of P.1, the variant from Brazil, B.1.1.7, the variant from the U.K., and B.1.427/429, the variant from California. Hassig also worries that visibility on those variants is being diminished as the number of coronavirus tests performed in the state is going down.

But Kanter said he thinks there are still enough tests being done to monitor viral spread.

“When you're below 5 percent positivity, you can be decently assured that you're doing enough testing,” he said.

The latest data from the health department shows a positivity rate of 3.6 percent.

The future of the pandemic isn’t just about how many people have already been vaccinated — it’s about the ongoing rates of new people choosing to get the shot.

If people were continuing to get vaccinated at high rates, there would be a significant difference in the number of people who’ve begun the process by getting their first shot, and those who’ve completed it by getting their second. (The two dose vaccines made by Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna remain the vast majority of all doses administered in the U.S.)

Instead, that gap is narrowing.

Over the month of April, when all adults were eligible for the vaccine, the gap has been halved. Across the state, there’s now only a slight difference of 4.5 percent between those who’ve begun the vaccine process and those who are fully vaccinated.

Hassig in part blames the slow-down on Gov. John Bel Edwards’s decision to drop the statewide mask mandate in late April. Without it, the state lost its leverage.

“I felt like that was our last carrot to kind of encourage people to get vaccinated,” Hassig said. “You know, get vaccinated, so we can drop the mask mandate, so you can attend the Saints games and the LSU games and, you know, all that sort of thing.”

Where access to the vaccine was an initial hurdle, the barrier to increasing vaccination now is one of ideology, Kanter said.

“Where people get their news and what their particular ideology is might be influencing their opinion on vaccinations,” he said. “I'm not happy about that. I think that's a really unfortunate reality.”

As the perception of the virus's threat diminishes, Straif-Bourgeois said the message to the public on why to get the vaccine becomes more altruistic: The less the virus spreads, the less chance it has to mutate and spawn deadly outbreaks such as the one in India.

“You have to think globally, and that's difficult,” she said.

There is one data point that matters more to Kanter than any other.

“If you were to pin me down and ask me for one data point that I put the most stock in at this point, with about 14 months experience in this pandemic, I would say the number of hospitalized patients with COVID throughout the state,” he said.

And that remains relatively low, at around 300 people.

If that changes, that’s when Kanter will worry.

“That's a real true measure you can't hide that has nothing to do with how much testing you're doing,” he said.

Copyright 2021 WWNO - New Orleans Public Radio